Home | Orchid sites | Galleries | Comments | Search

About Orchids

There are around 25,000 species of orchids in the world (about 10% of all flowering plants) but the figure is very uncertain. A more precise figure is not available since there all the time is changes. Old species splits into several new ones and new species are found constantly as botanists have the opportunity to study new areas. Most of the orchids are found in the tropical and subtropical areas. Besides the Antarctic there are orchids in all continents whereof Africa and Europe are the orchid poorest (in Africa about 1000 and Europe about 500 species).

The orchids belong to the monocotyledonous plants and are therefore more closely related to grasses, palms and lilies than to other flowering plants. Over half of the orchid species are "epiphytes", i.e. they grow on other plants, using them as support and clinging to the roots to keep themselves up. Often, they grow high up in the canopy to access the light. But in Europe all species are "terrestrial", i.e. they grow on the ground and have their roots in the soil.

The orchids are probably the plant group that has the most specialized pollination process. Most orchids are pollinated by insects that transfer pollen between the flowers. Often it is a very intricate interplay in where usually only a few, or sometimes only a single insect species, can perform a successful pollination. This makes the orchids very sensitive to environmental disturbances since it's not only the direct environment for the plant that have to be protected, but also factors important for the insect in question have to be taken into account.

Another factor that makes the orchids special, are their way of reproducing. A seed pod of tropical orchids can contain 2 million seeds. The seeds are therefore very small and they are spread like dust in the wind. They contain no nutrition to start the germ. The seed will get nutrient from a fungal partner but this fungi has to be present where the seed lands. If this happens, a symbiosis between the seed and fungi (mycorrhiza) begins a relationship that, in many cases, lasts the entire plant life.

About European Orchids

Compared to many of the tropical orchids, especially those usually grown at home, it seems that our European orchids are small and inconspicuous. One exception is the Lady's Slipper, that both in size and shape can match the tropicals.

There are hardly any plants in Europe that have been studied in such detail and for such long time that those from the orchid family. Still not all agree on how the structure should look like. What should be called species, subspecies or varieties? And still describes new species, usually after more accurate and extensive research on what previously was considered as variations within a species. DNA analysis, which is now being used to determine the relationship between species, has also led to major changes between some genera. All this means that, for an amateur, it is hard to get an accurate idea of the European orchid flora today. This also makes it difficult finding the right in older floras. Especially true is this for the Ophrys genus which is by far the largest in Europe.

All orchids in Europe are terrestrial, i.e. they grow in soil. Many are typical dry-land plants that have a short growing season, 3-4 months per year, and which survives with underground tubers during the remainder of the year, eg species from the genera Anacamptis, Ophrys, Orchis and some others. They grow and bloom in the spring when there is sufficient moisture in the soil and they have time to be pollinated and to set seed before the ground again is dried up.

Other species have a rhizome that roots grow out from and are therefore more similar to "normal" plants, e.g. the genus Epipactis. A few species are saprophytes that do not have their own chlorophyll, but live in symbiosis with a fungus partners, e.g. Neottia and Coralhorizza. These species have only a flower stalk above the ground to be able set seed.

Their coexistence with its fungal partner means that many orchids can survive underground for long periods. Best known is perhaps the saprophytic Epipogium aphyllum that frustrates many who seek this orchid. It may flower one year and then "disappear". Then it can live underground for several years before it once again appear with flowers.

Environments, threats and opportunities

All nature will change with time. Therefore, an area of some described as good orchid site, a few years later is "destroyed" in that respect. In the Mediterranean areas it may sometimes be grazing by sheep and goats that in a short term "destroy" any attempt by orchids to get up to a life above the ground. But also handed over to nature, phrygana and grasslands will be invaded by shrubs and dense maquis which will gradually shade out orchids and bulbs. This means that most orchid sites have its orchid richness in only a few years, while the environment is suitable.

One can never be sure that the information you got about orchid sites is paying off. Especially if the data is old.

But new sites also occur. Some examples are forest fires that open up surfaces that after a few years become suitable sites. Road construction, often criticized as destructive, creating open areas and edge zones, that left undisturbed and not herbicides sprayed or planted with "decorative garden plants", forming excellent environments for orchids. A big threat is the use of chemical herbicides and fertilizers. Especially the latter is used unwisely and arbitrarily so that spills and drainage affecting adjacent areas with catastrophic consequences for the natural flora. Orchids, along with most of the natural herbs, have small requirements for nutrition and cannot compete with fast-growing weeds and escapees from different crops that rapidly invade such nutrition-enriched environments. Many areas have lately been affected in this way.

In northern Europe, the changed farming methods led to that many species almost disappeared from some areas. The former small-scale agriculture created environments that favored many orchid species. When these environments either get overgrown or incorporated into large monocultures, environments are created that orchids cannot survive. This is true not for orchids only but many other plants have met the same fate. It is therefore very valuable those today established reserves or protected areas (although those are very small parts of what once existed) which attempts to restore / maintain environment necessary for maintaining diversity.

HYBRIDS and other abnormalities

Large populations of orchids in small areas make sometimes "mishaps" in nature, with hybrids as results. This is a phenomenon that one most often find within the genus Ophrys and make some difficult groups of species even more difficult. Common are populations of transitional forms between species in i.e. O. mammosa respectively. O. sphegodes groups, such as between O. mammosa and O. spruneri subsp. spruneri (Crete). In Northern and Central Europe we have the same problem with the Daztylorhiza genus where the different species frequently crosses each other.

It is often difficult to determine which parent species is in a hybrid. Some guidance can be obtained by studying the species in the local area but in terms of populations with transitional forms it sometimes happens that one of the parents, for some reason, has disappeared from the area. Sometimes, however, the parents' characteristics are clearly visible and it is clear that the hybrid has become something in between the parents..

Usually hybridization occurs between species within a genus, but in exceptional cases, crosses between species in related genera are reported. There are reports about hybrids at least between Anacamptis and Serapias and between Anacamptis and Neotinea.

However, one must not overlook the natural variation that exists within all species in terms of size, shape and color. Everything that deviates does not have a hybrid origin. There is also abnormal flower form due to environmental disturbances. Herbicides or other chemicals in the environment can produce strange results in plants. Most commonly "abnormalities" are color deviations and in literature there are countless names attached to descriptions of different color forms, as alba, albiflora, semi-alba, candida, chlorantha, nigra, rubra, bicolor, etc. Also different flower shapes leads to naming, such as Anacamptis pyramidalis var. brachystachys or f. augustiloba, which are forms that differ in terms of floral details and shape.

Sometimes you can find orchids with a strange look. There may be more than one lip, absence of lip, few or too many petals or similar. This may be due to various reasons. There may be a genetic change (mutation) in which case the phenomenon would recur at the next flowering. But it can also occur due to chemical or mechanical disturbance during the flower's development.

A phenomenon, which also is known from many other plants, is that among species which generally is self-pollinating new forms easily occurs. Among orchids this can be seen at Ophrys apifera which are mostly self-pollinating. Shortly after the flower opened up the pollinia will fall out of its protection down to the stigma and pollinate its own flowers. These phenomena have given name to several subspecies, varieties and forms, e.g. "jurana", "friburgensis", "botteronii", "trollii" and others.

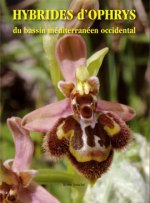

For those who have special interest in Ophrys hybrids, the following book may be of interest:

Rémy Souche: Hybrides d'Ophrys du bassin méditerranéen occidental (2008)

The book has an abundance of illustrations of Ophrys hybrids from western Mediterranean. At the beginning of the book there is a section with pictures of the parental species, which allows study of the similarities between the parents and the hybrid. But most of the 288 pages show full page photos of hybrids. The text is French but there is not much text, only a brief introduction. The captions contain only the Latin name and known locality. Softcover, 17 x 23 cm.